A version of this story first appeared in the April 22 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine.

PAUL SCHRADER (screenwriter) I had a series of things falling apart, a breakdown of my marriage, a dispute with the AFI, I lost my reviewing job. I didn't have any money and I took to drifting, more or less living in my car, drinking a lot, fantasizing. The Pussycat Theater in L.A. would be open all night long, and I'd go there to sleep. Between the drinking and the morbid thinking and the pornography, I went to the emergency room with a bleeding ulcer. I was about 27, and when I was in the hospital, I realized I hadn't spoken to anyone in almost a month. So that's when the metaphor of the taxi cab occurred to me — this metal coffin that moves through the city with this kid trapped in it who seems to be in the middle of society but is in fact all alone. I knew if I didn't write about this character I was going to start to become him — if I hadn't already. So after I got out of the hospital, I crashed at an ex-girlfriend's place, and I just wrote continuously. The first draft was maybe 60 pages, and I started the next draft immediately, and it took less than two weeks. I sent it to a couple of friends in L.A., but basically there was no one to show it to [until a few years later]. I was interviewing Brian De Palma, and we sort of hit it off, and I said, "You know, I wrote a script," and he said, "OK, I'll read it."

Just months after Martin Scorsese completed shooting Taxi Driver on the streets of New York in 1975, the New York Daily News ran its infamous front-page headline: "Ford to City: Drop Dead." The president had denied a federal bailout to New York, then on the brink of bankruptcy. The movie captures that nadir in the city's history: As his cab glides through the rain-soaked streets, as ominous in its ruthless forward movement as the shark in Jaws, Robert De Niro's Travis Bickle, a lonely Vietnam vet, eyes the pimps and drug dealers choking the sidewalks and intones, "Someday a real rain will come and wash all the scum off the streets." Those mean streets have long since been scrubbed clean, but Taxi Driver, which will celebrate its 40th anniversary with a screening reuniting the filmmakers at the Tribeca Film Festival on April 21, has lost none of its disturbing power. In Paul Schrader's screenplay, born out of his own moment of crisis, Bickle first obsesses over Cybill Shepherd's campaign worker, a cool, unobtainable beauty, and when rebuffed, tries to become an avenging angel, watching over Jodie Foster's teen prostitute. Pauline Kael called the movie "one of the few truly modern horror films." It went on to earn four Oscar nominations — for De Niro and Foster, composer Bernard Herrmann and best picture, only to lose that big prize to the more rousing, upbeat Rocky.

MICHAEL PHILLIPS (producer) [My then-wife] Julia and I were living on Nichols Beach, and our next-door neighbors were Margot Kidder and Jennifer Salt, and Brian De Palma was living with Margot at the time. Brian said to me one day, "There's this guy who has written a screenplay. It's not really for me, but I think it's your taste." It was incredibly pure, a very honest piece of work. So I went to my two partners at the time, Julia and Tony Bill, and proposed we acquire it for $1,000, and by a two-to-one vote — Tony and I voted to acquire it, and Julia voted against it — we acquired the option.

MARTIN SCORSESE (director) Brian gave me the script. I reacted very viscerally, almost mystically to it and its tone and the struggle of the character. But I was still trying to get them to take me seriously as a filmmaker. I'd done a low-budget independent film called Who's That Knocking [at My Door] and an exploitation film for Roger Corman called Boxcar Bertha. I liked Julia a lot, but she kept pushing me away, dismissive, but funny. She'd just tell me, "Come around again when you've done something more than Boxcar Bertha."

PHILLIPS It took several years to get made. One day Paul suggested we see a rough cut of [Scorsese's] Mean Streets, and midway through, I really felt this is our guy. Johnny Boy [played by Robert De Niro] is our actor. So we made a proposal to Marty and Bob's agent. They both had to do it or neither. I mean it was silly, in retrospect.

ROBERT DE NIRO (Travis Bickle)We all liked the script a lot and wanted to do it and were committed to it.

From left: De Niro, Foster and Scorsese on the set of Taxi Driver

De Niro, as Travis Bickle, fantasizes in front of a mirror. “It was a long scene in the first cut. And everybody was saying, ‘Cut the scene. It goes on forever, Marty,’ ” Schrader recalls. “Fortunately I had the right answer: ‘Why don’t you cut it in half and use it twice?’ ” And so portions of the scene appear at two points in the film.

MICHAEL CHAPMAN (cinematographer) I realized years later that it's a kind of folk tale or urban legend. It's a werewolf movie in a weird way. Even his hair changes. There are these things that are wandering around in the night that are dangerous. In this case, the werewolf saves the girl, instead of killing the girl.

PHILLIPS We went about trying to shop it, and it was rejected. Then Marty went off to do Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore and Bobby went off to do Godfather [Part II] and 1900.

SCORSESE I remember Robert De Niro winning that Oscar for Godfather: Part II. That night Francis Coppola accepted for Bob, who was shooting another film, and I was there, and Francis told me, "It's going to be good for your film."

PHILLIPS By then, Marty and Bob were very viable filmmakers, and we were able to set it up at Columbia Pictures on a very small, million-and-a-half-dollar budget. One of the things that pushed it over the top was that the talent hung in at bargain-basement prices. De Niro got $35,000, Marty got $65,000, producers got $45,000 and Paul got $30,000. Columbia was run by David Begelman, and he pulled the trigger. But David was nervous about it, even at a low price.

SCHRADER I had written the character of the pimp [that Harvey Keitel plays] as black, and we were told by Columbia we had to change it to a white guy because the lawyers were concerned "if we do this and Travis kills all those black people at the end, then we're going to have a riot. And we're going to be liable for this."

Casting the 12-year-old Foster to play the underage Iris also raised red flags.

JODIE FOSTER (Iris) I had done Alice [with Scorsese]. He called my mom about the part, and she thought he was crazy. But I went in to meet him for an interview. My mom thought, with my school uniform on, there was no way he'd think I was right for it. But he said yes, and she trusted him.

PHILLIPS We had to get approval from the Los Angeles welfare board, and we were running into a roadblock, so we hired Pat Brown [former governor of California] as an attorney, and magically the problem went away.

FOSTER Part of the deal was that any scenes that felt uncomfortable sexually, they would have an adult be a stand-in. So my sister Connie, who was over 18, stood in for a couple of over-the-shoulder shots.

PHILLIPS At the last minute, Columbia felt they needed more star power, and that's how Cybill Shepherd came in.

CYBILL SHEPHERD (Betsy) When I got the script, my character had no lines, and I threw it across the hotel room, aiming for the garbage can. But because of Mean Streets, I trusted De Niro and Scorsese. My agent at the time, Sue Mengers, told me, "When you go in to the interview, one, don't talk, and, two, do your hair and makeup."

Foster, who played the underage prostitute Iris, says, “I’m just so grateful to have been part of something that’s really an American classic, part of our golden age of cinema, which to me really is the ’70s.”

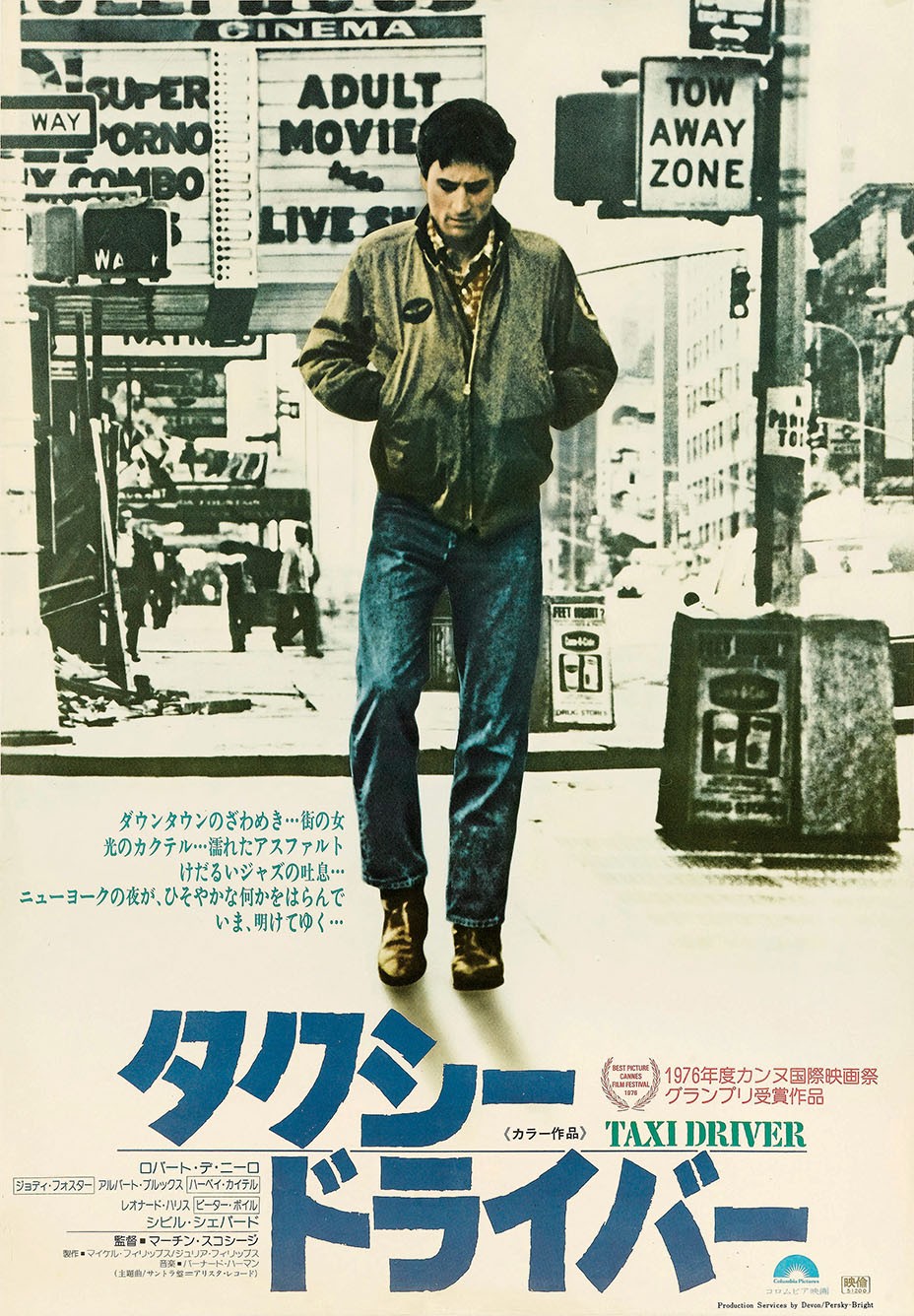

A Japanese poster for the film.

With filming set to begin in June 1975, De Niro had just two weeks after he completed Bernardo Bertolucci's 1900, which he'd been filming in Italy, to prepare for his new role.

DE NIRO I'd met with Marty in Cannes while I was shooting 1900, and we went over the script. And I worked with some guys on a military base in Northern Italy on the accent. Then I flew back to New York and started driving a cab and getting ready to shoot.

FOSTER As a kid, I thought it would be a job like all the others, but when I got there, I realized it was creating a character from scratch, which I'd never done before. I'd just been asked to be myself. It was eye-opening for me. Robert De Niro and I had a bunch of outings, where he took me to different diners around town and walked through the script with me. After the first time, I was completely bored. Robert was pretty socially awkward then and was pretty much in character, which was his process. I think I rolled my eyes at times because he really was awkward. But in those few outings, he really helped me understand improvisation and building a character in a way that was almost nonverbal.

SCHRADER During pre-production, I headed uptown, just talking to people on the street, looking for the great white pimp, and in the middle of it all I ended up at a working girl's bar and struck up this conversation with this girl [Garth Avery] who was kind of strung out and very, very thin. Very close to this character that I wrote. I asked her to come back to the hotel — we were staying at the St. Regis because it was cheap — and told her I'd pay her, but it was not about sex. Around 7 o'clock in the morning, I slipped a note under Marty's door that said, "I'm going downstairs to have breakfast with Iris. You must join us." We watched her pour sugar on top of her jam, the way she talked, and a lot of that is in the diner scene in the movie.

FOSTER She plays the girl who stands next to me in the street in the movie. I talked to her a little bit, but they were more interested in her mannerisms, how she dressed and walked. I hated my costumes, though. At the fitting, I was sniffing back tears because I had to wear those dumb shorts, platform shoes and halter tops. It was everything I hated. I was a tomboy who wore knee socks. But I got over it.

SHEPHERD That Diane von Furstenberg wrap dress I wear, that was my own dress that I brought to the set.

Once filming began on the streets of New York, so did problems with the studio.

SCORSESE The streets were packed with people, and the heat was quite extraordinary. At night, it was even worse. You get a sense of that in the film where the kids are playing with the fire hydrant. It was always raining, so it was always wet and the windows had gems of water gleaming out at us.

CHAPMAN [The movie's style] was very much influenced in my mind, and in Marty's too, by [Jean-Luc] Godard and [his cinematographer] Raoul Cotard. Much of the way the movie looks was dictated by the fact that we didn't have a lot of time and didn't have a lot of money and therefore couldn't do traditional things. We couldn't light the streets with big lights. We had to take our level of light down to let New York light itself. Of course, that turned out to be exactly the right thing to do, and I was eager to do it in a terrified sort of way. Thank God we didn't have anymore time or money.

DE NIRO I remember shooting on 59th and Ninth [Avenue], and it was very slow, working my way through the traffic.

CHAPMAN We were in a real cab, in real New York. We weren't even towing the cab behind any sort of generator truck. It was just Bobby driving the cab through the streets of New York. Marty and I would squat in the back [of the cab] with the [camera] operator shooting over Bobby's shoulder. We had a little one-ten battery pack in the trunk. We stuck the sound man in there, poor guy, and we'd just drive off into the streets.

When George Memmoli, the actor who was to play a man stalking his wife who hails a ride with Travis, was injured on another movie, Scorsese agreed to play the part himself. Says Schrader, “I was afraid that Marty would see himself and would be so mortified he would cut himself out of the movie, and I liked the scene. But I was a hundred per- cent wrong. He saw it, loved it and kept every single bit of himself in.”

From left: Scorsese, Schrader and Phillips during shooting of the film.

SCORSESE The problem was that [scenes] didn't match when it rained. After the first week, there was a big confrontation [with the studio] where I refused to shoot until I got the permission to get as much as I could against the window [in one of the diner scenes]. There was a constant problem staying on schedule. I think we ended up with 45 days, five or six days over.

PHILLIPS We built Travis' apartment and Iris' apartment in condemned buildings. We had to hire a gang to protect us from other gangs. It was very arduous. It was a tight schedule, we were over from the beginning, and there was lot of pressure from the studio.

SCORSESE Michael Phillips absorbed a great deal of that. For example, I shot De Niro in this porno theater on Eighth Avenue, and there's a reverse in which you see the pornography on the screen. I was going to put a drop of oil on the negative to obscure the image, but in order to do that I had to get the image first. They saw the film at the studio [before I could obscure the image] and up comes the pornography, and they were furious. So they yelled at Michael. No matter what I did, it irritated everyone.

PHILLIPS He blew that. He really blew it. He could have shot that without having to go through that little drama we went through.

When George Memmoli, the actor who was to play a man stalking his wife who hails a ride with Travis, was injured on another movie, Scorsese agreed to play the role himself.

SCORSESE De Niro told me I should do it, and everyone was against it. But I was thinking that it was a labor of love, a film that was made for us and not a popular film in the sense that we could take chances and see what happened. If worse comes to worst, we could reshoot with another actor.

DE NIRO There was no one else to do it, as I remember it, and I was happy with Marty doing it.

SCORSESE Bob was very instrumental because he pointed out to me that the first line of dialogue was "Turn off the meter." And I did one take, and he said to me, "When you say 'Turn off the meter,' make me turn it off. Just make me turn it off. I'm not going to turn it off until you convince me that you want me to turn off that meter." So, I learned a lot. He sort of acted with the back of his head, but he encouraged me by not responding to me. And using that tension of the inherent violence, I was able to able to take off and riff some dialogue.

SCHRADER I was afraid that Marty would see himself and would be so mortified and cut himself out of the movie, and I liked the scene. I said to Michael and Julia, "Marty is going to cast himself in this role and he's going to see it and he's not going to like it and then he's going to cut the scene out!" I was 100 percent wrong. He saw it, he loved it, and he kept every single bit of himself in.

Scorsese, in the back seat of the cab that De Niro drove through the streets of New York. “I remember shooting on 59th and Ninth [Avenue], and it was very slow, working our way through the traffic,” says De Niro.

De Niro’s Travis confronts Betsy (Shepherd, in a dress of her own) in the campaign office as Scorsese offers direction. When he was in character, Shepherd recalls, “De Niro was truly frightening. And that makes acting very easy, when somebody is that good.”

SCHRADER Bob called me and said, "Well, in the script, it says that he pulls out the gun, looks at himself, talks to himself. Well, what's he saying?" I said, "He's just a kid in front of a mirror playing with his gun. Just make up stuff." I figured whatever he made up would be better than writing those kind of lines.

SCORSESE It was the last week of shooting. We were in a building that was about to be torn down on Columbus Avenue and 89th Street. We were running behind schedule, and I knew Bob would have to say something to himself in the mirror, and I honestly didn't know what it would be. I just remember squeezing in this scene on that angle that you see in the film, the head-on angle. I was sitting at Bob's feet, and then he just started talking to himself. So I just kept encouraging him to do that.

DE NIRO I was having difficulty with the gun, but we got it and that was used in the scene. The mirror thing was just something that I improvised that felt right. Marty was always good and easy about trying things.

SCORSESE After about an hour and a half, our assistant director was pounding on the door to say we've got to get going. I opened the door and said, "Please, just give us another 15, 20 minutes. We've got something really good here."

When the film was completed and shown to the executives at Columbia, further problems developed.

SCORSESE We had one screening at the studio in a small screening room for some friends, and then it was shown to the studio. I don't recall what my friends said, but people were kind of perplexed. I believe it was the next day that the studio saw it and there was a smiling kind of reaction that was very brief. Then I heard word that they were concerned that women wouldn't like the film. Then, what had happened was that the film was shown to the MPAA and it was given an X rating. There was no way the studio was going to release an X, understandably. I had the same problems with Mean Streets. I'm used to it. We were told we were going into a meeting and the studio was going to discuss with us how to proceed. We sat down, took out a pen, and the studio exec turned to us and said, "Cut it for an R or we cut it." Then we were dismissed.

PHILLIPS I ended up showing it many times to the MPAA ratings board with moderate, minuscule changes. You become inured, so you see the same scene and the same blood and "Oh yeah, it's a lot better now." Ultimately Marty desaturated the red, and that made a big difference. And I don't know if it was a good thing or not, but I kind of like it. I like it that way.

SCORSESE I was furious. I was complaining about it and telling all my friends and colleagues. At that time I was talking a lot to Eric Pleskow and Mike Medavoy, over at United Artists, and I remember being at the MGM commissary, complaining, and they said, "Tell you what. We'll take the picture sight unseen with an X." So I called my producers and said UA would do that. But they were unsure of the legal problems, though crazier things have happened. So it may have been a matter of a few weeks, but I trimmed some of the blood scenes. And I was obsessed with this idea of desaturation that [cinematographer] Oswald Morris used in John Huston's Moby Dick and I always wanted to do it. So I asked, "What if we drained some of the color out and replicated the process of Moby Dick?" That was accepted by the studio, and so the entire shootout at the end goes to a grainier look. And I just finally felt good about the picture. In fact, the opening Colombia Pictures logo is the same. It's very grainy. I can't tell you how many times when they've done LaserDiscs and then DVDs, they would say, "Now you can use the original Columbia logo without the grain," and I would say, "No the grain's supposed to be there! Leave it be!"

PHILLIPS There wasn't a lot of enthusiasm. The studio decided to release it in two theaters in February [1976] and hope it did a little business.

SCHRADER Columbia had an investment in young talent more than they had in the film, so they were not going to do anything that would create enemies — bur they did not think it was going to be successful. Michael and Julia had a dinner at the Sherry [Netherland Hotel] in New York for Bob, Marty and I the night before it opened and basically Michael said, "I think we made a really terrific film and no one knows what will happen tomorrow. But whatever happens let's not start blaming each other, but accept the fact that we made this film and it didn't work financially." I had been in a car with Charlie Powell, who was the head of publicity for Columbia, like a week before, and I'd said to him, "I think this film is going to do well, I'm starting to get that vibe." And he said "No, the film's not going to do well." And I said "I'll make you a bet." And he said "OK" and I said "I'll bet you 20 bucks." In those days, they could break down opening day and opening weekend by the amount of advertising they put in. I was told that they had paid for a $40,000 weekend and they got a $65,000 one. As soon as that happened, everything changed. And Charlie paid up.

Opening in New York on Feb. 8, 1976, Taxi Driver was an immediate critical and commercial hit, grossing $28.8 million domestically ($117.9 million today). It was then invited to the Cannes Film Festival.

FOSTER I was in the middle of shooting Freaky Friday. Columbia didn't want to pay for me to go to Cannes, but my mom said, "Look, this is an amazing opportunity. She speaks French. We'll pay for it ourselves." Then the whole issue about violence in the movie kind of exploded. Marty, Bobby and Harvey kind of got stuck at the Hotel du Cap and didn't come out very much. But I ended up working the whole time, and the studio was very nice and said, "OK, we'll pay for your flight."

SCORSESE One of the trade papers ran a story that Tennessee Williams, who was head of the jury, hated the film, so we went home. Before we went home, though, we were given a dinner by Costa-Gavras and Sergio Leone, who were on the jury, and they really liked the film a great deal.

PHILLIPS I stayed behind, so when we won, I accepted the award — half the audience was on its feet cheering and the other half was booing.

SCORSESE I got a call from [publicist] Marion Billings around 5 in the morning saying, "You've won the Palme d'Or." We thought we might get screenplay or best actor for De Niro, so it was very surprising.

As a guide for cinematographer Michael Chapman, Scorsese drew a series of sketches (above) that mapped out the entire film, including the climactic shootout (below).